Gifted people make bad teachers

At Maven, one of my roles is to find instructors, so I’ve thought a lot about what makes someone a good teacher.

People most commonly screen for signals of competence and credibility. In tech, proxies are brand-name companies or experiences: FAANG1, exited founders, early tenure at rocketship startups, etc. In academia and education: test scores, an Ivy League diploma or two, advanced degrees.

If you’re only thinking about credibility, I think you end up with the Masterclass model of instructor – learn gymnastics from Simone Biles, write a coming-of-age novel with Judy Blume, cello basics with Yo-Yo Ma.

But for the best instructors, I think subject mastery is necessary but not sufficient. While I agree that a level of mastery is required to be a strong teacher, I think the ability to transfer your knowledge effectively is as important as having the knowledge to begin with.

I often find that people who are gifted in an area are the least able to teach on that subject. For the purpose of this essay, let’s say a “gift” is a subject or ability that you have never struggled to excel at – people might have told you that you were “talented”or “a natural” in this area. Examples from people I’ve met recently: you have a natural ear for/are quick to pick up languages, you’ve never struggled with hand-eye coordination, you have an excellent memory for names and faces, etc.

Here’s why I think “gifted” people are the least equipped to teach on their gift:

Being a good teacher means that you need empathy for the experience of struggle. Gifted people are less likely to have experienced this frustration in their gifted area and may be more prone to impatience when students get stuck.

Understanding the “struggle” of mastering a subject also means predicting when and where students will get stuck – common pitfalls or misconceptions, steps in the process where a student might struggle to connect A to B. If you’ve never encountered these pitfalls, you’re unable to predict how, when, and where they occur for others, making you ill-equipped to help someone else overcome these roadblocks.

(To be clear – I’m not saying Simone Biles never struggled in becoming the best gymnast in the world. I’m just saying that if you’re trying to learn how to do a cartwheel, the person to ask might not be the person for whom doing a cartwheel now comes as easily to as breathing.)2

Conversely, all the subjects I’ve struggled with (and subsequently achieved a level of competence in), I’ve emerged with both knowledge of both #1 and #2, plus:

A delight for mastering something I struggled with and an appreciation for the rewards of my effort – which I believe translates into the way excellent teachers talk about their subjects.

I taught middle school math for two years, and one of my favorite experiences of being a teacher was coaching the competition math team at my school. I don’t think I was a particularly gifted math student – I’m certainly competent, god bless my immigrant parents, but I struggled a fair bit through most of my math classes in high school.3

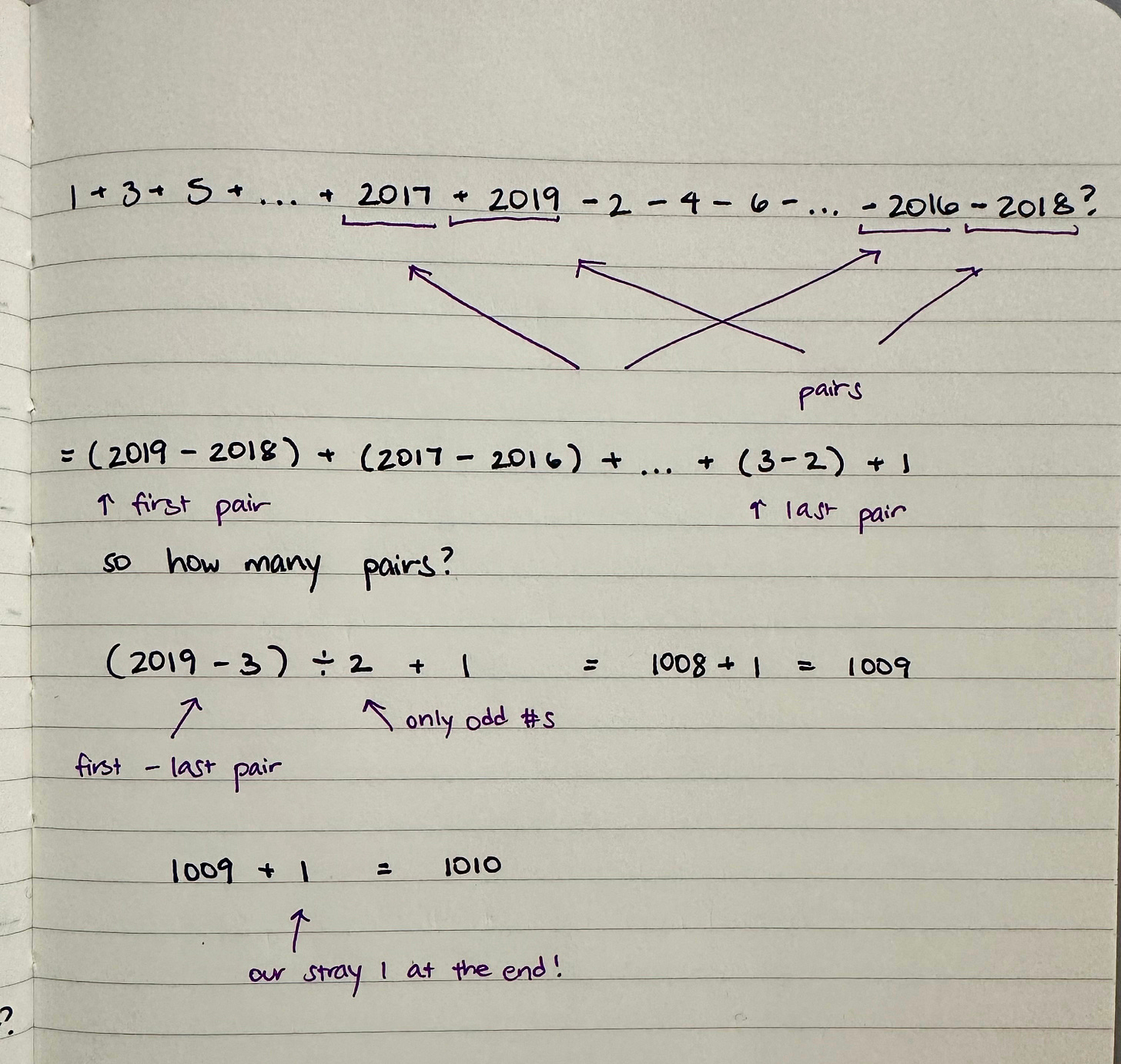

The joy for me in teaching competition math was reliving the experience of these problems: first, total confusion as a student looked at a problem that was seemingly impossible. The frustration of staring at the problem for a little longer, maybe trying the obvious “brute force” route and quickly realizing it would take forever. Maybe a moment of rage – “I can’t believe Ms. Claire is giving us this INSANE problem to solve! I HATE math!”

Then curiosity, as someone (me) reframed the problem for them. Maybe instead of doing 1000 arithmetic problems, you can find a pattern to solve it more quickly instead. That initial flutter of excitement when they spotted the pattern – if you add parentheses, its the same problem over and over again! A little momentum, the feeling at the top of a rollercoaster when the cart tips over the peak and teeters on the verge of speeding downwards – and the rush when they solve the problem with three more little steps. A little flair to circle answer option E, pencil down.

Because I knew what the big mental “jumps” were to solve this problem, I had different hints and pointers prepared at each step, plus a few different ways to lay out the “jump” if the student missed the leap the first time. Understanding the emotional journey each student took while looking at this problem helped me choose from my menu of encouragements: sometimes a soothing word, sometimes a helpful hint or a praise for effort, sometimes tactful silence when they were unraveling something on their own, and of course, gleeful affirmation and delight when they solved the problem.4

A pattern I see in the best instructors I talk to is this theme of: “I want to teach the course I wish I’d had earlier in my career.” Occasionally I’ll hear from someone who wants to teach on a personal strength of theirs, but that strength is always reinforced by the processes, tactics, templates, frameworks, and experiences that this person accumulated as they struggled to get to the 1% in this area.

People seem to resonate the most with the things they had to work to understand or achieve – these are the areas where I see the most passion and energy from instructors to give back to students who are in their shoes.

I guess it’s a good reframe for struggle. You might be really in the weeds of something right now, but it’ll probably make a good Maven course in a year.5

MAANG? MAMAA? Whatever.

This also opens up a question of: how many levels above you is your optimal teacher? This is a post for a different day.

When I told my parents I’d be teaching math, my dad very seriously looked at me over his glasses and said: “Have you told them about that C you got in multivariable calculus?”

This is the human side of teaching that I don’t think AI has mastered yet. More on this later.

At which point you should definitely email me: claire@maven.com.